The 2015 United Nations Climate Change Conference opens in Paris today. This is the 21st ‘Conference of the Parties’ or COP since the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) was adopted at the Rio Earth Summit in 1992.

Since then each year, without fail, governments have discussed when, where and how much to cut greenhouse gas emissions and to engage in the mitigation of and, increasingly, adaptation to the impacts of climate change.

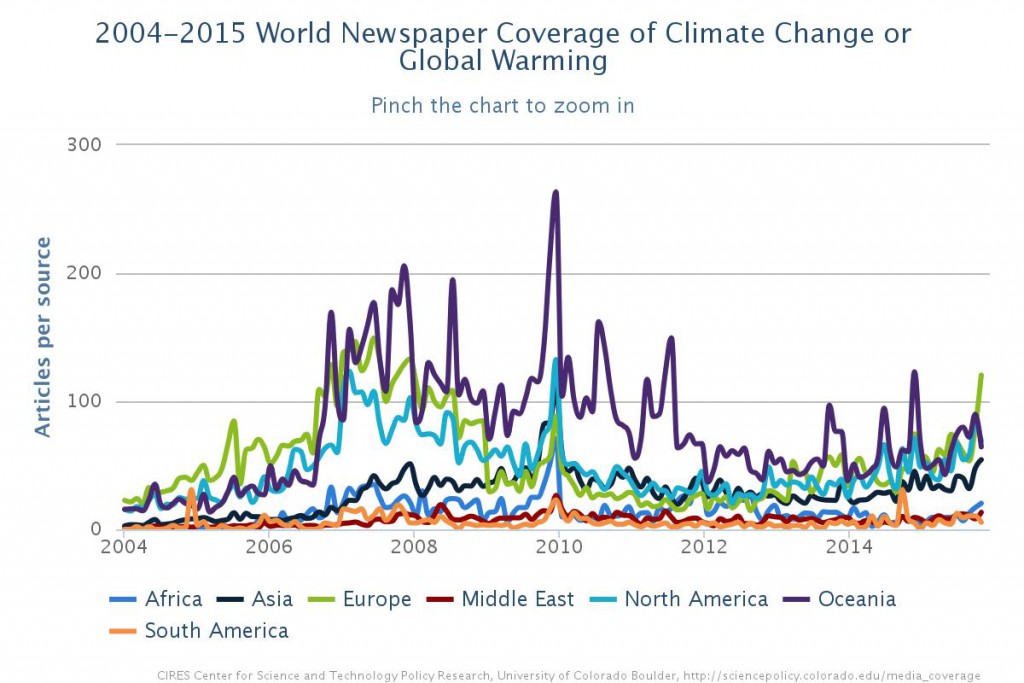

Gradually, but indeed rather slowly, discussions have moved forward. But there has also been a set-back: in COP15 the 2009 Copenhagen summit – things “turned sour”. Between 2006 and 2009 climate science had become increasingly confident in diagnosing that there is a problem called climate change (or rather a complex bundle of such problems) and this diagnosis had increasingly begun to influence political and public thinking. It had almost become a matter of common sense to think that climate change poses problems to the global and local governance of the planet we live on.

However, at the end of November 2009, six years ago, private emails between climate scientists were made public without their authors’ consent, and they were mined for quotes that could cast doubt on the credibility of climate scientists and climate science. The emerging climate change common sense was shaken and indeed fractured for a while after what became known as the ‘climategate’ affair.

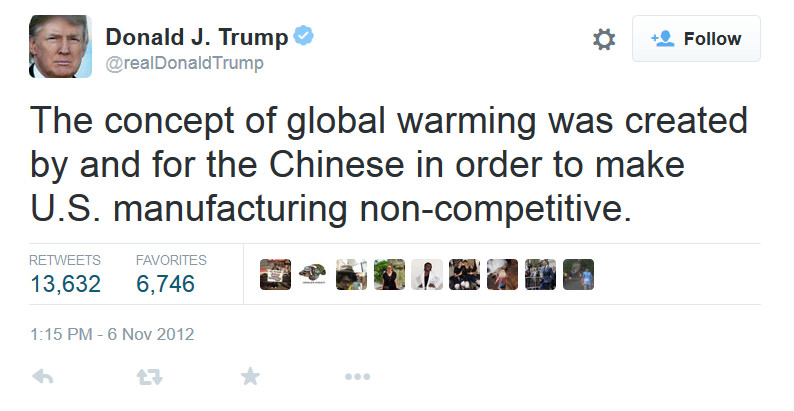

Since then there “has been a significant shift in understanding of the scale of the climate challenge by scientists, politicians and the public”, and while efforts are still being made to cast doubt on the credibility and integrity of climate scientists, most recently by US Rep. Lamar Smith (R-TX), such efforts seem no longer able to undermine an emerging global sense of urgency any more, at least in the United States. A recent survey by the Center for Climate Change Communication at Mason University in the United States has found that the majority of Americans think it is important to reach an agreement in Paris this year to limit global warming.

This means that despite world carbon emissions falling for a variety for reasons, a low-carbon world is not yet around the corner. Although it seems that politicians worldwide have begun to accept that scientists have done their job and that it’s now their turn to do theirs, their thinking and planning is still governed by political rather than scientific pressures, by short-term rather than long-term visions. Why else would the UK government, for example, axe a £1bn grant for developing new carbon capture and storage (CCS) technology and why would the Department for Energy and Climate Change downgrade “its expectations for each of the main low-carbon sources of electricity”. Such political decisions are just what they are: political.

However, there are other factors, which contribute to public support declining for a tough climate deal. In some countries around the world, worries about the economy and terrorism are stronger than worries about climate change. There is nothing scientists, whether natural or social, can ‘do’ in this context, unless they are invited into the process of decision making on realistic terms. Once invited in, scientists should no longer be expected to (endlessly) demonstrate that climate change is a problem; rather they should be allowed to use their energy and expertise to explore ranges of context-sensitive solutions. There are signs that such collaborations are happening or at least being called for.

In the 2015 context of a world faced with multiple crises, political actions intent on undermining the credibility and integrity of climate scientists, based on allegations that their work is politically or financially motivated, might almost seem frivolous. However, there is a larger problem, namely that thinking, yet again, about climate change might also seem almost frivolous. To talk about climate change in this new world of political and economic tensions is fraught with difficulties. As Hugo Rifkind expressed so well: “the overall vibe is one of weary angels dancing on a pinhead.” It would probably not take much to topple those angles.

While there are still advocates for non-action and while politicians might still decide that for whatever reasons of political exigency non-action is the best way forward in the short-term, such thinking and acting is being increasingly challenged. There is some chance then that common sense might return to these political negotiations in Paris and the weary angels might be able to continue dancing on a pinhead.

One can only hope that freed up from having to prove that climate change is a problem, climate scientists, together with social, cultural and communication scientists, can be involved with politicians and citizens in talking about and, in particular, sketching out possible solutions or solution scenarios. How wide or narrow the scope for such solutions is, depends entirely on politics and publics, not on science.