The dramatic reduction in flights during the COVID-19 pandemic opens a natural opportunity for us to consider: what role does the aviation industry have to play in tackling the climate crisis?

Before the pandemic, it seemed unthinkable: a 70 percent drop in flights worldwide? Yet this is exactly what happened in May 2020. The dramatic changes seen in our lifestyles since the beginning of 2020 disposes of the idea that radical change is not possible. Under the right pressure, industry, governments and individuals seem to adapt their priorities to comply with external conditions. Climate change – as COVID-19 – is a global crisis. There can, and will, be radically different lifestyles which we adopt in response to this externality.

Aviation accounts for approximately 3.5 percent of radiative forcing, with the release of NOx as well as CO2 being particularly significant. Luckily(!) we have a plethora of global actors who negotiated an international agreement with which to minimise the global temperature increase. It logically follows: the only way to accomplish decarbonisation consistent with the Paris agreement targets is to actively scale down energy use. (Please let’s put out of our minds false solutions such as NET technologies, see my post on BECCS). What could that look like?

-

- Directly: among other things (for example, resource use) we should actively scale down unnecessary industries – those which are clearly not needed for human wellbeing.

- Gradually: not an option! (We’re already in the crisis).

The aviation industry could be considered to fit into the “unnecessary industry” category. This is not a call to ban all air travel, just that we evaluate its position in a “climate-just” society. I would like to calmly assess our modern-day relation and perspective of flying. It is time that we examine our transportation system and think, is a plane really the right tool for the job?

Domestic flights: senseless and dispensable

The acceptance of air travel as an appropriate means of transport has reached farcical limits. The 170km journey from Nuremberg to Munich, for example—both located within the region Bavaria (Germany)—has a train connection that takes 1 hour, 5 minutes. Yet somehow this route sees approximately 2,500 flights per year. I cannot help but find this baffling.

If we are serious about enacting changes that fall in line with the Paris agreement pledges, it seems that domestic flights are utterly incompatible with these demands. A paper released earlier this year found that emissions from aviation could consume 27 percent of the carbon budget that we have to limit warming to 1.5 degrees if growth continues as predicted. Whilst there are bound to be some technological advances in efficiency, it is necessary to state the obvious: we need to fly less. But a call for reducing the number of flights isn’t about flight shaming or looking at one’s individual actions. Whilst it’s all well and good to turn off your lightbulbs or consume less beef , individual lifestyle changes tend to address the symptoms rather than the cause of the problem; and the downscaling of the aviation industry fits in well with system change as proposed by the degrowth movement. This is about recognising that continued growth in these industries is harmful and unnecessary, especially when there are existing infrastructures that act as a more climate friendly alternative.

What are other impacts of degrowth in aviation?

An important and frequent question in response to this change in industry is: what about the jobs? Scaling down the number of flights means there will be less work in this field. Proponents of degrowth however, have answers to this, with one namely being to reduce the working week. With an economy that requires less labour, the working week can be shortened, and the remaining labour can be distributed more evenly.

Can you imagine a world without flying?

There are a whole host of cultural reasons linked to why we fetishize flying in the global North. Once related to status, wealth and social position, despite the cramped conditions of a budget airline flight, jetting off on a place retains glamour. Halfway through writing that sentence, I already myself was unconvinced. There’s really not much glamour in having a fight to sit in the fire exit for just a bit more leg room, paying a fiver for a soft drink, or hauling your tired body to the remotely located airport at 6 in the morning to then stand in various security queues for 2 hours. I am more convinced that the sheer affordability of flights in Europe make it such an appealing option. It is therefore necessary not only to reduce flying, but at the same time to make the alternatives more accessible.

Climate justice

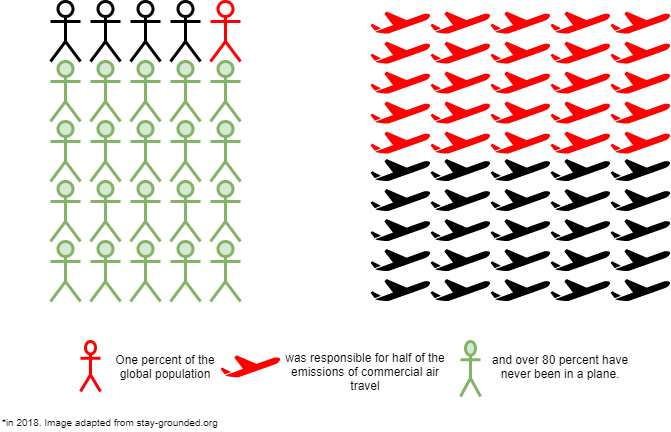

Finally, I would like to reference the fact that flying remains an incredibly privileged mode of transport. The disparity and unequal distribution of wealth is clearly illustrated when considering that one percent of the global population is responsible for more than half of commercial aviation emissions. Despite the normalisation of flying to Western Europeans, it is still a relatively new development, and remains inaccessible to the majority of the global population. Whether due to restrictive migration policies, or access to infrastructure, approximately only ten percent of the global population has ever been on a plane.

<< Ideas on how we can better think about how we travel do not end (or begin) here! If you have 40 seconds, please watch the clip by #BikeIsBest, who explore the theme very neatly, and have a look at the great initiatives and information by Stay Grounded. >>