As world leaders continue negotiations at COP21 in Paris, apparently close to sealing some sort of deal to fight climate change – the future of nations’ energy production is an essential consideration, if this conference is to result in meaningful change, rather than just an increase in hot air.

A recent study at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research predicted that if we were to burn all remaining fossil fuel below ground, it would melt nearly all of Antarctica’s ice leading to a 50 or 60 meter rise in sea levels. One hopes humanity avoids such a fate.

In the mid mid-90s, a terrible post-apolocalyptical movie starring Kevin Costner (with gills) called Waterworld was released. The film imagined a world in which the ice caps had melted, submerging most of the earth’s surface below water and leaving the few remaining humans desperate to discover the mythical Dryland. It’s safe to assume most people would like to avoid a future involving no land, or Kevin Costner as our saviour.

A key step in the fight against climate change is for nations to switch from “dirty” energy production such as burning coal and oil to clean renewable energy sources like wind, hydro and solar.

There are many countries who are now on board with this. In Paris, India unveiled an alliance of 120 countries committed to embracing solar power. Renewable energy technologies have existed for many decades and the environmental reasons for making the transition are extremely compelling. Yet some countries are very slow to make the shift. Why is that?

For both developed and developing nations alike, one of the major barriers to switching to renewables is… (drum roll): money. The set-up costs for renewable infrastructure are often extremely high and the roll-out of such technology may take many years.

There’s also the issue of generator capacity. It may take as many as 2077 2-megawatt wind generators to generate the same amount of power as a single nuclear reactor. This is part of the reason that despite strong public sentiment against nuclear power in Germany, the Government cannot simply switch off the eight remaining reactors which still generate 16 percent of the nation’s energy.

One of the sticking points in previous climate summits has been the amount of money developed nations contribute to developing nations to help them reduce their carbon footprint. While the transition for dirty energy to renewables may be slow and costly, one has to say, it’s kind of a price worth paying.

Another reason for the slow transition to renewables is the power and influence wielded by mighty oil and gas companies.

As it stands, the playing field between fossil-fuel and renewable energy companies is not even remotely fair. In 2014 fossil fuels agencies received around $550 billion in subsidies world-wide. Sustainable energy agencies, by comparison, received only $120 billion.

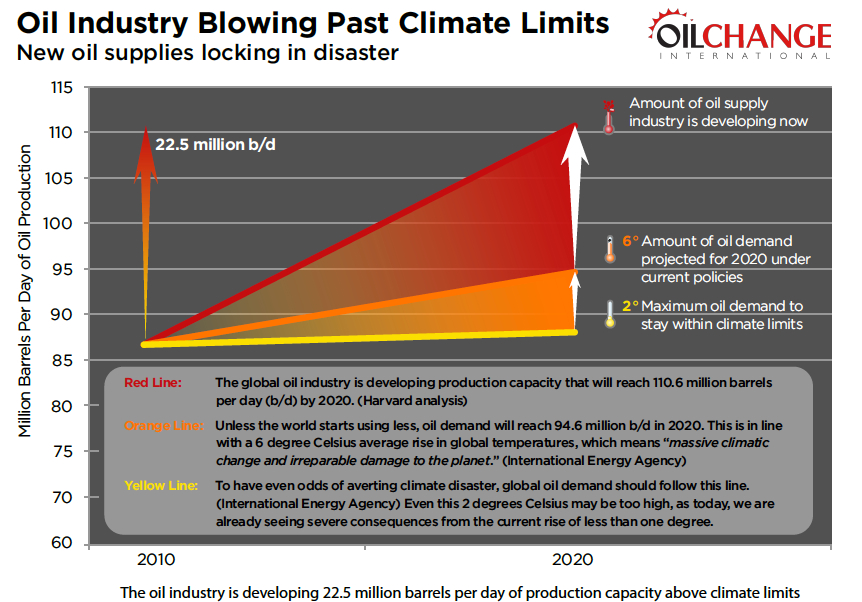

The oil and gas industries are major employers. A 2011 report by the American Petroleum Institute (API) said there were 9.8 million full-time and part-time U.S. jobs in oil and gas that accounted for 8 percent of the U.S. economy. That kind of workforce gives an industry influence. Few rational people would advocate for instantly shutting oil and gas industry immediately. After all, oil is used in vast numbers of consumer products most of us enjoy and changing to alternatives will take time. The argument, therefore is that we need to shift towards renewable energy sources much faster than we currently are (see graph below).

The oil and gas lobby have practically endless resources to influence politicians, particularly in the US (see here). The industry are unlikely to kill the goose that lays the golden eggs while the money is still flowing, even though the price of oil has recently dropped significantly.

By their nature, governments and politicians focus on the short-term and winning the next election. When it comes to saving the planet – thinking about the short-term is the last thing we need.

Last year The International Energy Agency singled out the Middle East as a region where fossil fuel subsidies are hampering renewables. According to their report, every day 2 million barrels per day are burnt to generate power that could otherwise come from renewables. Such renewable would be competitive if oil wasn’t heavily subsidised. It takes bold political leadership for a nation to opt for several years of low or negative economic growth in order to transition to cleaner sources of energy production and to construct the necessary infrastructure. The real question is – in the long-term, can any nation afford not to make the change? Economic growth is a rather useless pursuit if the planet on which we all live is no longer able to support life.

In Beijing, residents are now accostomed to “code red” smog alerts where the city’s streets are ruled off-limits, factories are closed down and cars are banned from driving until the pollution subsides. I experienced this myself on a visit to China last year. After only a few days in Beijing, my lungs became deeply congested. See this real time air pollution monitor and note the cities around the world that have either red or dark red number above them.

Saving the environment while stimulating growth are not mutually exclusive pursuits. There are already countries that demonstrate achieving both simultaneously is possible. So who are these countries?

Well, Sweden and Germany for starters.

In the 4th edition of the Global Green Economy Index report, the two nations came up trumps. The report examined factors such as efficiency, markets and investment as well as climate leadership and the quality of nation’s natural environments. It also included how green countries were perceived to be by experts (Germany was first, Sweden third) verses how well they performed in reality (Sweden first, Germany fourth). Sweden is so good at recycling its waste – it actually imports garbage. Germany proved how quickly a country can make the transition to renewable energy. Between 2000-2014 Germany went from just 6 percent to around a third of total energy coming from renewables.

So would a country like China – currently the world’s biggest carbon emitter, consider slowing down or event halting its fantastic economic growth to transition to a greener economy? Right now, it seems highly unlikely. They have made some progressive moves such as spending more than any other nation investing in green technology last year but under current targets, they won’t peak their carbon output until 2030.

Should we exchange temporary economic growth for the long-term health of the planet?

In this TED talk climate researcher Anna-Bows Larking cites her own study saying that in order for us to prevent exceeding Earth’s climate budget: “economic growth needs to be exchanged, at least temporarily for a period of planned austerity in wealthy nations.” She makes the point that carbon emissions tend to be cumulative and can potentially remain in Earth’s atmosphere for more than a century. This means if we don’t undertake significant cuts in our carbon emissions now, we will have to make much more drastic cuts in the future.

In 2012 this paper about transitioning to a green economy was presented to the United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development. The conclusion of the report stated:

“Some sectors will feel the pain of transition, and countries that specialize in those sectors will be challenged accordingly. But while the individual losers are clearly important, it is also important to put the pain of adjustment into perspective. As noted above, it has been well documented that the costs of action are far less than the costs of inaction. In the long run, perpetuating unsustainable livelihoods is not in anyone’s interest.”